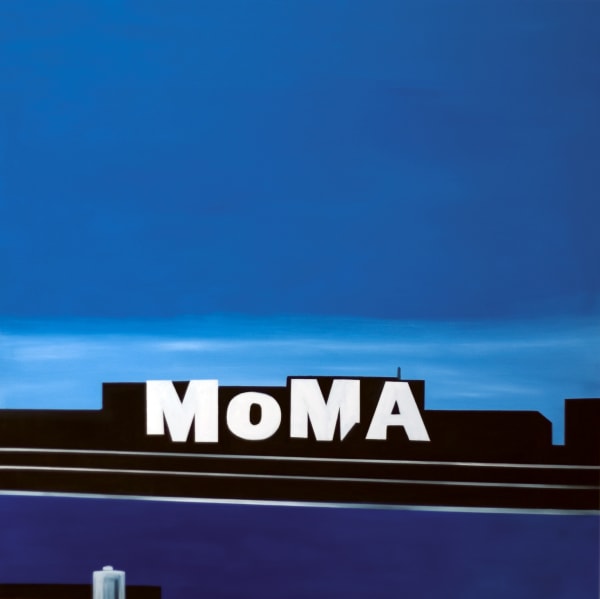

The Museum Collection: GS, Frankfurt, Germany

Museums occupy a precious place within the terrain of architectural forms and functions. As containers for material culture that overtly seek to distil representations of the society in which museums reside, museum architecture is perhaps the most emblematic of all. Historically, with the advent of nineteenth century modernity, museums were seen to enter the lineage of the temple. They became first and foremost secular places of worship, where heritage is made tangible so that it might tell us about ourselves and further about those that went before us: spaces where memory is ostensibly materialized. Traditionally museums are solid and immovable in their outer structure. While exhibitions may be, and increasingly are, transitory, the site of display is largely static. Art museums offer a further step on this esoteric journey of cultural representation. In the current climate of art practice, the sites of production of art and its display are contested, almost to the point of undermining art itself. Artists such as Marcel Broodthaers presented a critique through his art since the 1960s, while Thomas Hirschhorn is a more recent and persistent devotee of defying the modernist dream of a solid neutral temple for culture in which to contain art as artefact.

Back in the mainstream, both history and art museums are often viewed as sculptural works in themselves. The work of contemporary architects such as Frank Gehry and Daniel Libeskind moves unapologetically closer to art, as perceptible in either the aesthetic play of the former and the symbolic priorities of the latter. Despite Gehry’s claim that the relationship between architecture and art is not necessarily one of succession, but one of inspiration (he suggests that painting is the highest form of art, one from which he draws creatively), his buildings are viewed as awe-inspiring sites in themselves – an experience usually reserved for the nature kept outside architecture’s confines or for the art held within its walls. The notional distinction between art and architecture generally revolves around varying perceptions of spatial function and its ever-changing relation to form. The modernist ethos declared its conclusion through its promotion of the white cube, a triumph of architectural neutrality over nominal function, while the new architects having cleared the fence of this modernist desire to present pure functional form, now openly toy with the renewed tension between art and architecture. Evident in the use of a variety of materials for material’s sake, the pleasure of visual manipulation for its own sake and an overt recognition of spatial symbolism, this amounts to an overall drive to well and truly see off the lonely limitations of a functionalist aesthetic.

Eamon O’Kane has chosen to re-look at the master buildings, and master not mistress they usually were, of a high modernist moment (for example, the Guggenheim, New York), and to commingle this view with recently transformed buildings (the Baltic, Newcastle), and further to speculate on the new art-itecture (the Guggenheim, Bilbao). His endeavour attests to the fact that the culture of the present is always inclusive of an amalgamation of the past. The contemporary view includes all it can survey and it is with a knowing intention that O’Kane has reversed Gehry’s one-way traffic of inspiration, choosing to draw creatively from architecture and its image for his art. In The Mobile Museum, O’Kane has developed an installation that penetrates the ideals of architecture, exploits the reproduced image of various buildings, and has generated a body of works that builds upon his curiosity regarding the notion of rupture between fact and fiction, experience and representation. To do this, O’Kane employs a range of media, and as with any artist of depth, he discloses a consistency in interrogative interests sustained from earlier work.

Extract from

Art as Spatial Resistance by Niamh Ann Kelly is an art writer, critic and lecturer at the Dublin Institute of Technology.

-

Eamon O'Kane, Museum Collection: How soon is now? (Museum Frieder Burda, Baden Baden), 2005

Eamon O'Kane, Museum Collection: How soon is now? (Museum Frieder Burda, Baden Baden), 2005 -

Eamon O'Kane, Museum Collection: There is a light that never goes out (Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark), 2005

Eamon O'Kane, Museum Collection: There is a light that never goes out (Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark), 2005 -

Eamon O'Kane, Museum Collection: Ziggy Stardust (Guggenheim, Bilbao), 2005

Eamon O'Kane, Museum Collection: Ziggy Stardust (Guggenheim, Bilbao), 2005 -

Eamon O'Kane, The End (Guggenheim, New York), 2005

Eamon O'Kane, The End (Guggenheim, New York), 2005 -

Eamon O'Kane, The Robots (Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin), 2005

Eamon O'Kane, The Robots (Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin), 2005 -

Eamon O'Kane, Ideal Collection, 2005 - present

Eamon O'Kane, Ideal Collection, 2005 - present -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-